Gaius Florius Lupus asked in a related thread: "The idea that there is no positive pleasure beyond the avoidance of pain always was what bothered me most about Epicurus' ethics, because it would lead to apathy. Do you have a quote where he specifies the kind of pleasure beyond absence of pain we should seek to attain? I only know quotes where he warns us of "unnatural desires"

Because this issue is so important I wanted to respond in a separate thread. Another way of asking the question is: "What references does anyone have to offset what appear to be the clear statements in the Letter to Menoeceus, in PD3: "The limit of quantity in pleasures is the removal of all that is painful," and in PD18: "Once the pain arising from need is removed, physical pleasure is not increased and only varies in another direction." Why does this not add up to a call that there is nothing higher than the extinguishment of desire,an ascetic "zero state"?

It is always good to talk about this because it is necessary to piece together other material in order to arrive at a total context that allows all of Epicurus's statements on pleasure to be reconciled. Because the quotes Gaius Lupus asked about do seem to make it appear that Epicurus held "pleasure" to be something different from what normal people think it means. We know in fact that Epicurus defined "gods" as being natural and not supernatural, and he defined "virtue" as being instrumental to pleasure and not as absolute. Was Epicurus using a technical definition of the word "pleasure" to convey to us that he considered "absence of pain" to be a complete and true description of the "pleasure" that he held to be the goal of life?

I have collected all of my research at the link I will provide below, but I can summarize a couple of very important points, especially as this relates to the issue of "katastematic" pleasure, which is the name most commentators seem to give to believe that Epicurus used to describe this type of "zero state / absence of pain" pleasure.

Of the material directly attributed to Epicurus, we know that Epicurus was emphatic that "pleasure" is a feeling which we experience personally and need use no words to define or to defend. This seems to be a clear statement that pleasure is something all animals, including humans, experience without need for explanation: From On Ends: "...pleasure he holds to be the Chief Good, pain the Chief Evil. This he sets out to prove as follows: Every animal, as soon as it is born, seeks for pleasure, and delights in it as the Chief Good, while it recoils from pain as the Chief Evil, and so far as possible avoids it. This it does as long as it remains unperverted, at the prompting of Nature's own unbiased and honest verdict. Hence Epicurus refuses to admit any necessity for argument or discussion to prove that pleasure is desirable and pain to be avoided. These facts, be thinks, are perceived by the senses, as that fire is hot, snow white, honey sweet, none of which things need be proved by elaborate argument: it is enough merely to draw attention to them. (For there is a difference, he holds, between formal syllogistic proof of a thing and a mere notice or reminder: the former is the method for discovering abstruse and recondite truths, the latter for indicating facts that are obvious and evident.) Strip mankind of sensation, and nothing remains; it follows that Nature herself is the judge of that which is in accordance with or contrary to nature."

As to the highest pleasure we have this recorded in Athenaeus – Deipnosophists XII p. 546E: Not only Aristippus and his followers, but also Epicurus and his welcomed kinetic pleasure; I will mention what follows, to avoid speaking of the “storms” {of passion} and the “delicacies” which Epicurus often cites, and the “stimuli” which he mentions in his On the End-Goal. For he says “For I at least do not even know what I should conceive the good to be, if I eliminate the pleasures of taste, and eliminate the pleasures of sex, and eliminate the pleasures of listening, and eliminate the pleasant motions caused in our vision by a visible form."

We know that Epicurus said this about pleasure as the good: Plutarch, That Epicurus actually makes a pleasant life impossible, 7, p. 1091A: Not only is the basis that they assume for the pleasurable life untrustworthy and insecure, it is quite trivial and paltry as well, inasmuch as their “thing delighted” – their good – is an escape from ills, and they say that they can conceive of no other, and indeed that our nature has no place at all in which to put its good except the place left when its evil is expelled. … Epicurus too makes a similar statement to the effect that the good is a thing that arises out of your very escape from evil and from your memory and reflection and gratitude that this has happened to you. His words are these: “That which produces a jubilation unsurpassed is the nature of good, if you apply your mind rightly and then stand firm and do not stroll about {a jibe at the Peripatetics}, prating meaninglessly about the good.”

And we know that Cicero wrote that Epicurus held "joy" to be the greatest good: Cicero, Tusculan Disputations,III.18.41: "Why do we shirk the question, Epicurus, and why do we not confess that we mean by pleasure what you habitually say it is, when you have thrown off all sense of shame? Are these your words or not? For instance, in that book which embraces all your teaching (for I shall now play the part of translator, so no one may think I am inventing) you say this: “For my part I find no meaning which I can attach to what is termed good, if I take away from it the pleasures obtained by taste, if I take away the pleasures which come from listening to music, if I take away too the charm derived by the eyes from the sight of figures in movement, or other pleasures by any of the senses in the whole man. Nor indeed is it possible to make such a statement as this – that it is joy of the mind which is alone to be reckoned as a good; for I understand by a mind in a state of joy, that it is so, when it has the hope of all the pleasures I have named – that is to say the hope that nature will be free to enjoy them without any blending of pain.” And this much he says in the words I have quoted, so that anyone you please may realize what Epicurus understands by pleasure."

Several modern authorities have reached the conclusion that this zero state / absence of pain is not to be construed as some new type of pleasure, different from what we normally understand the word "pleasure" to mean.

Gosling & Taylor, “The Greeks on Pleasure.” 1982. See Chapter 19, “Katastematic and Kinetic Pleasures” (Also :“Plato’s and Aristotle’s intellectual feats can only win one’s admiration, but a cool look at the results enables one to understand how Epicurus might have seemed more in contact with the subject. For if we are right, Epicurus was not advocating the pursuit of some passionless state which could only be called one of pleasure in order to defend a paradox. Rather he was advocating a life where pain is excluded and we are left with familiar physical pleasures. The resultant life may be simple, but it is straightforwardly pleasant.”)

Boris Nikolsky, “Epicurus on Pleasure.” 2001 (“The paper deals with the question of the attribution to Epicurus of the classification of pleasures into ‘kinetic’ and ‘static’. This classification, usually regarded as authentic, confronts us with a number of problems and contradictions. Besides, it is only mentioned in a few sources that are not the most reliable. Following Gosling and Taylor, I believe that the authenticity of the classification may be called in question. The analysis of the ancient evidence concerning Epicurus’ concept of pleasure is made according to the following principle: first, I consider the sources that do not mention the distinction between ‘kinetic’ and ‘static’ pleasures, and only then do I compare them with the other group of texts which comprises reports by Cicero, Diogenes Laertius and Athenaeus. From the former group of texts there emerges a concept of pleasure as a single and not twofold notion, while such terms as ‘motion’ and ‘state’ describe not two different phenomena but only two characteristics of the same phenomenon. On the other hand, the reports comprising the latter group appear to derive from one and the same doxographical tradition, and to be connected with the classification of ethical docrines put forward by the Middle Academy and known as the divisio Carneadea. In conclusion, I argue that the idea of Epicurus’ classification of pleasures is based on a misinterpretation of Epicurus’ concept in Academic doxography, which tended to contrapose it to doctrines of other schools, above all to the Cyrenaics’ views.“)

Mathew Wenham On Cicero’s Interpretation of Katastematic Pleasure in Epicurus. 2007 “The standard interpretation of the concept of katastematic pleasure in Epicurus has it referring to “static” states from which feeling is absent. We owe the prevalence of this interpretation to Cicero’s account of Epicureanism in his De Finibus Bonorum Et Malorum. Cicero’s account, in turn, is based on the Platonic theory of pleasure. The standard interpretation, when applied to principles of Epicurean hedonism, leads to fundamental contradictions in his theory. I claim that it is not Epicurus, but the standard interpretation that generates these errors because the latter construes pleasure in Epicurus according to an attitudinal theoretical framework, whilst the account of pleasure that emerges from Epicurean epistemology sees it as experiential.”

Norman DeWitt, “Epicurus and His Philosophy.” 1954 Chapter 12, the New Hedonism (e.g.: Even at the present day the same objection is raised. For instance, a modern Platonist, ill informed on the true intent of Epicurus, has this to say: “What, in a word, is to be said of a philosophy that begins by regarding pleasure as the only positive good and ends by emptying pleasure of all positive content?” This ignores the fact that this was but one of the definitions of pleasure offered by Epicurus, that he recognized kinetic as well as static pleasures. It ignores also the fact that Epicurus took personal pleasure in public festivals and encouraged his disciples to attend them and that regular banquets were a part of the ritual of the sect. Neither does it take account of the fact that in the judgment of Epicurus those who feel the least need of luxury enjoy it most and that intervals of abstinence enhance the enjoyment of luxury. Thus the Platonic objector puts upon himself the necessity of denying that the moderation of the rest of the year furnishes additional zest to the enjoyment of the Christmas dinner; he has failed to become aware of the Epicurean zeal for “condensing pleasure.”)

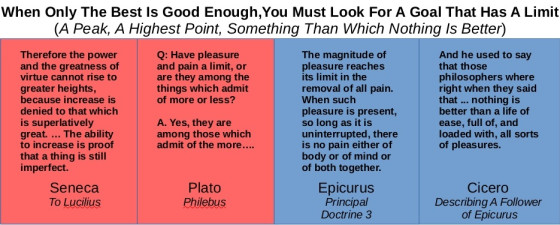

So those cites can be used to show that "pleasure" means the same thing to us as it did to Epicurus. As to why Epicurus was insistent on discussing pleasure as absence of pain, I would contend that that was in response to the reasoning of Plato in Philebus, and others who attacked the feeling of pleasure as something which can never be satisfied, as collected at my link here: