Happy Twentieth of May!

Epicurus is famously known to written: “To sea with your swift ship, blessed boy, and flee from all education (paideia, also translated as culture).” This remark come to us with no context, as our only source is D.L. 10.6, which combines it with a slam from Epictetus, translated at Perseus this way: “And in his letter to Pythocles : “Hoist all sail, my dear boy, and steer clear of all culture. Epictetus calls him preacher of effeminacy and showers abuse on him.”

Because the traditional commentaries since the Epicurean age have been written by Stoics and other anti-Epicureans, this passage has been used to bolster the argument that Epicurus advised that we should live in isolation, figuratively (if not literally) walling ourselves off from the outside world.

Norman DeWitt rejected that argument as follows, concluding that it was Epicurus goal – not to retreat – but to establish a new culture which would compete with the prevailing culture:

DeWitt continues with his analysis in Chapter Two of his book, but for purposes of this post I just want to emphasis the ramifications. Epicurus devoted his life to an extensive campaign of book-writing, letter-writing, and lecturing. We know little about the personal life of Lucretius, but what we do know is that his “On The Nature of Things” was a monumental effort. Of the other Epicurean lives we know enough about to cite, we know that Titus Pomponius Atticus was extensively involved in the cultural affairs of his time, and we know that Gaius Cassius Longinus was intimately involved in the political affairs of his time. One could argue that the absence of knowledge of the details of the lives of the greater number of Epicureans is evidence of their choice to live obscurely, but there is nothing in the surviving literature to indicate that an isolated or uneducated or hermetic lifestyle was extolled as an example for Epicureans to follow.

What we have instead is the great body of Epicurean philosophy, which when taken seriously leads to the opposite conclusion. Those who took Epicurus seriously will also take their own lives seriously, and lived those lives to the fullest extent possible. If we start with first principles, how can we not live our lives as vigorously as possible? Consider just a few of the Epicurean starting-points:

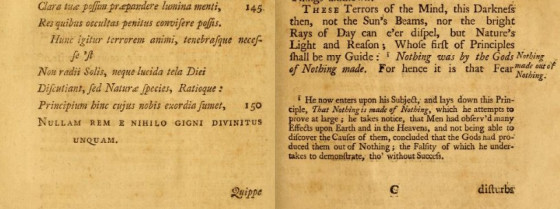

- There are no supernatural gods steering the universe for us or against us – neither the universe, nor we ourselves – are slaves to inexorable fate.

- To the contrary, like the universe itself, we are ourselves composed of combinations of elemental particles which are controlled only by natural principles, much of which is within our power to understand and to shape.

- What is not within our power is to stop the motion of these particles, and there is no final place of rest for them, or for us – so we know that our lives must be lived and our goals must be achieved during the limited time when we can sustain our own individual combination of particles.

- Not only are the elemental particles always in motion, but the universe itself is not only eternal in time but infinite in space, so we know that there can be no central point, no overarching creating god, from which any perspective can be viewed as permanent or final. It is therefore absurd to suggest that there is any “absolute truth” or “universal reason” or realm of “ideal forms” against which our own feelings of pleasure and pain may be compared and found invalid.

----------

As Seneca recorded: Sic fac omnia tamquam spectet Epicurus! So do all things as though watching were Epicurus!

And as Philodemus wrote: “I will be faithful to Epicurus, according to whom it has been my choice to live.”

Additional discussion of this post and other Epicurean ideas can be found at EpicureanFriends.com.