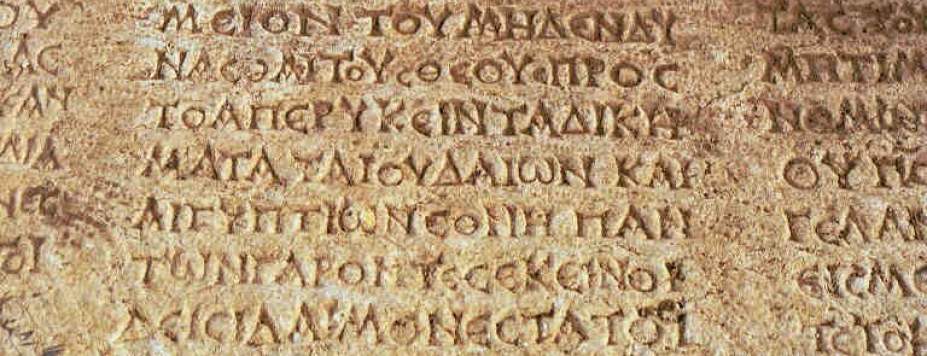

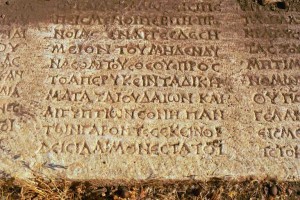

Having already reached the sunset of my life (being almost on the verge of departure from the world on account of old age), I wanted, before being overtaken by death, to compose a fine anthem to celebrate the fullness of pleasure and so to help now those who are well-constituted. Now, if only one person or two or three or four or five or six or any larger number you choose, sir, provided that it is not very large, were in a bad predicament, I should address them individually and do all in my power to give them the best advice. But, as I have said before, the majority of people suffer from a common disease, as in a plague, with their false notions about things, and their number is increasing (for in mutual emulation they catch the disease from one another, like sheep) moreover, it is right to help also generations to come (for they too belong to us, though they are still unborn) and, besides, love of humanity prompts us to aid also the foreigners who come here. Now, since the remedies of the inscription reach a larger number of people, I wished to use this stoa to advertise publicly the medicines that bring salvation. These medicines we have put fully to the test; for we have dispelled the fears that grip us without justification, and, as for pains, those that are groundless we have completely excised, while those that are natural we have reduced to an absolute minimum, making their magnitude minute.

Having already reached the sunset of my life (being almost on the verge of departure from the world on account of old age), I wanted, before being overtaken by death, to compose a fine anthem to celebrate the fullness of pleasure and so to help now those who are well-constituted. Now, if only one person or two or three or four or five or six or any larger number you choose, sir, provided that it is not very large, were in a bad predicament, I should address them individually and do all in my power to give them the best advice. But, as I have said before, the majority of people suffer from a common disease, as in a plague, with their false notions about things, and their number is increasing (for in mutual emulation they catch the disease from one another, like sheep) moreover, it is right to help also generations to come (for they too belong to us, though they are still unborn) and, besides, love of humanity prompts us to aid also the foreigners who come here. Now, since the remedies of the inscription reach a larger number of people, I wished to use this stoa to advertise publicly the medicines that bring salvation. These medicines we have put fully to the test; for we have dispelled the fears that grip us without justification, and, as for pains, those that are groundless we have completely excised, while those that are natural we have reduced to an absolute minimum, making their magnitude minute.

Translation by Martin Ferguson Smith

The best sources of information on Diogenes’ inscription include:

-

Diogenes of Oinoanda, a page by Harold Roig i Gorina. (start your review of the inscription here!)

- Epicurus.info Page on Diogenes of Oinoanda (best source for the largest amount of the remaining text)

- German Archaeological Institute Page on Oinoanda

- Wikipedia on Diogenes of Oinoanda

- Livius.org Page on Diogenes of Oinoanda

- Photos from Oinoanda

The following presentation is a summary of the Epicurean Inscription of Diogenes of Oinoanda, prepared as a project of NewEpicurean.com in August of 2013. What you are about to hear is a selection based on portions of the translations by Martin Ferguson Smith and C. W. Chilton of the remaining fragments of the Inscription. This presentation is not a literal reading, but a version rendered into modern American English and organized for audio presentation. The purpose of this presentation is to reconstruct the general argument left to us by Diogenes of Oinoanda. Only the general ideas essential to that argument are included here. In a few cases, brief additional material from the letters of Epicurus have been added to maintain the flow of the argument and compensate for the fragmentary state of the text. For additional detail, the student of Epicurus should consult Smith’s and Chilton’s full translations of the fragments, as well as the ultimate authority, the text from the wall in its original Greek. MP3 version available here.

THE ELEMENTAL MESSAGE OF THE INSCRIPTION (paraphrased version)

I, Diogenes of Oinoanda, a friend of Athens, hereby inscribe for you, on this wall, my summary of Natural Philosophy.

Most men suffer from false notions about the nature of things, and they fail to listen to their body even though it brings a just accusation. For the body accuses the soul of dragging it to pursue things which are not necessary, even though the Natural desires of the body are small, and easy to obtain. These men do not understand that, while the soul can live well by sharing in the Natural enjoyments of the body, many of the desires of the soul are both extravagant and difficult to obtain. These desires are not only of no benefit to our nature, but actually are dangerous to us.

In my life, I have observed many men in this predicament. I have mourned for their behavior, and wept over their wasted lives. I have therefore composed this inscription, because I consider it a part of wisdom for a good man to give benevolent assistance, to the utmost of his ability, to those men who are capable of receiving it.

In my own case, I have now reached the sunset of my life, and I am on the verge of departing from it due to old age. But before I die, it is my desire to compose for you this anthem to celebrate the fullness of happiness, and to help those who are benevolent and capable of receiving its message.

Vain fears of death, and of the gods, grip the majority of men. Such men fail to see that true pleasure does not come from the approval of the crowd, or from perfumes, or ointments, but from the study of nature. And so I write to refute those who say that the study of nature is of no benefit to us. Even though I am not engaging in public affairs, the inscription on this wall will serve as my testimony to you, that what truly benefits our nature — freedom from disturbance — is identical for one and all.

If only a few people were gripped by vain desires, and by false fears of death and of the gods, I would address them individually, and do all in my power to give them my best advice. But as I have said, a great multitude of people suffer from the same disease, as if in a plague. Great numbers suffer from false notions about the nature of things, and the number who suffer is increasing. In mutual emulation, many men catch this disease from one another like sheep. In addition to my fellow-citizens who are in this predicament, I desire to help future generations, for they too, though unborn, belong to us, as do any foreigners who may happen to come here.

The inscription on this wall has been set up to reach a large number of people, and I will use it to advertise publicly the medicines that bring salvation. These medicines we Epicureans have fully tested, for we ourselves have dispelled the fears that grip other men without justification. We have completely cut away those pains that are groundless, and those pains that are natural we have reduced to an absolute minimum.

But I must warn you against other philosophers, especially those, like the Socratics, who tell you that studying natural science, and investigating celestial phenomena, is a waste of time. I must warn you also against those who are ashamed to make that argument explicitly, but who use other means of telling you the same thing. When such philosophers argue that it is not possible for us to be certain of anything, and that the nature of things is impossible to apprehend, what else are they saying than that there is no need to pursue the study of natural science? After all, what man will choose to seek something that he believes he can never find?

I warn you also against Aristotle, and those who hold the views of his Peripatetic School. These men say that nothing is scientifically knowable, because all things are continually in “flux,” and this flux is so rapid that all things evade our ability to apprehend them. We Epicureans, on the other hand, acknowledge that all things are in motion, but we deny that this motion is so rapid as to prevent our senses from being able to grasp the true nature of things. Indeed, the Aristotelian position is absurd. Who could ever say that some things are now white, and some are black, but that, at another time, things are neither white nor black, if they did not in fact first have certain knowledge of the nature of both “white” and “black?”

It is our Epicurean position that Nature is composed of first bodies, called “elements,” which have existed, and will exist, eternally, without beginning or end. These elements are indestructible, and possess unchanging properties, and from them all things in the universe are generated. Since neither god nor man can destroy these elements, we conclude that they have always been, and always will be, indestructible forever, and the elements and their properties will always remain beyond the reach of what some men call “Fate,” or “Necessity.” For if these elements could be destroyed in accord with “Fate”, all things would have long ago perished, since an infinite amount of time has already passed before we were born.

We Epicureans also maintain that the things that we see are real. For this point I will use as my witness the evidence that we see when we look in mirrors. When we look in a mirror, we would not see ourselves if there were not a continual stream of elements, flowing from us to the mirror and returning back to us. The image that we observe in the mirror is proof that particles stream steadily from all things, retaining the shape of the object from which they were emitted.

These images flow from all objects, and, because they impinge on our eyes, we are able to see external realities, and to have those impressions enter our minds. Once seen, our minds are rendered susceptible to receiving similar images. Even when the original object is no longer present, our minds are prepared to receive images of similar objects in the future.

This flow of images continues even when we are asleep. When we sleep, our senses are, as it were, paralyzed and extinguished. The mind, however, which still stirs, is unable to test what it receives against the evidence of the senses, and thus, in dreams, it conceives a false opinion about these images. At such times, the mind is mistaken, and thinks it is apprehending true realities. Errors arise in dreams because our senses sleep when our bodies sleep, and our senses provide our only rule and standard, by which we must always judge what is true and what is false.

Now let us also discuss the movements of the stars and planets in the sky. Let me first emphasize, however, that we must treat things that are far away from us much differently than those things which we can examine closely. When we investigate phenomena that we cannot examine closely, it frequently occurs that the evidence supports several different explanations for that phenomena. Where the evidence supports more than one possibility, it is reckless and wrong to pronounce that only a single possibility is correct. The disposition to grasp at one among several possibilities, when the proof is insufficient, and when several possibilities may be true according to the evidence, is characteristic of a fortune-teller, or a priest, or a fool, and not the path of a wise man. Where evidence is not sufficient to be sure of our choice, we must wait for additional evidence before judging. Until then we should say only, as the case may be, that more than one explanation is possible, or that one explanation is more plausible than another.

The important point to take from the study of physics is that the universe did not arise at random from chaos, nor was it created, or is it controlled, by any gods. But do not take from this that we Epicureans are impious, or that we fail to have sympathy for those who have false opinions about the gods. Men who experience false visions, but who are unable to understand how they are produced, are understandably apprehensive, and they convince themselves that these visions were created by the gods. Such men vehemently denounce even the most pious men as atheists. As we proceed, it will become evident to you that it is not the Epicureans, who deny the true gods, but those who hold false opinions about the gods. For we Epicureans are not like those philosophers who categorically assert that the gods do not exist, and who attack those who hold otherwise. Nor are we like Protagoras of Abdera, who said that he did not know whether gods exist, for that is the same as saying that he knew that they do not exist. Nor do we agree with Homer, who portrayed the gods as adulterers, and as angry with those who are prosperous. In contrast, we hold that the statues of the gods should be made genial and smiling, so that we may smile back at them, rather than be afraid of them.

Let us reverence the gods, and observe the customs of our fathers, but let us not impute to the gods any concepts that are not worthy of divinity. For example, it is false to believe that the gods, who are perfect, created this world because they had need of a city, or needed fellow-citizens. Nor did the gods create the world because they needed a place to live. To those who say such naive things, we ask in turn: “Where were the gods living beforehand?”

Those men who hold that this world was created uniquely by the gods, as a place for the gods to live, of course have no answer to this question. By their view, the gods were destitute and roaming about at random for an infinite time before the creation of this world, like an unfortunate man, without a country, who had neither city nor fellow citizens! It is absurd to argue that a divine nature created the world for the sake of the world itself, and it is even more absurd to argue that the gods created men for the gods’ own sake. There are too many things wrong, with both the world and with men, for them to have been created by gods!

Let us now turn our attention from gods to men.

Many men pursue philosophy for the sake of wealth and power, with the aim of procuring these either from private individuals, or from kings, who deem philosophy to be a great and precious possession.

Well, it is not in order to gain wealth or power that we Epicureans pursue philosophy! We pursue philosophy so that we may enjoy happiness through attainment of the goal craved by Nature.

We shall now explain to you the identity of this goal set by Nature, and we will explain how it can not be obtained by wealth, nor by political office, nor by fame, nor by a life of luxury and sumptuous banquets, nor by the pleasures of choice love-affairs. Only through philosophy can we secure Nature’s goal. Thus we shall set the whole question before you, here, on this wall. We have erected it in public, not for ourselves, but for you, citizens, so that you might have it in an easily accessible form.

But know this also: We Epicureans bring these truths, not to all men whatsoever, but only to those men who are benevolent and capable of receiving this wisdom. This includes those who are called “foreigners,” though they are not really so, for the compass of the world gives all people a single country and home. But it does not include all people whatsoever, and I am not pressuring any of you to testify thoughtlessly and unreflectively. I do not wish you to say, “this is true,” if you do not agree with us. For I do not speak with certainty on any matter, not even on matters concerning the gods, without providing you evidence, and the proper reasoning to support what I say.

And so I address each of you! Even if you are indifferent and listless, do not be like passers-by in your approach to this inscription! Do not consult it in a patchy fashion, and fail to take the time to understand the overall system!

Here is the point at issue between the other philosophers and the Epicureans. If we were both inquiring into, “what is the means of happiness?” and the other philosophers wanted to say, “the virtues,” (which would actually be true), it would not be necessary for us to take any other step than to agree with them.

But the issue is not, “what is the means of happiness?” The issue is, “what is happiness?” Or, in other words, “What is the ultimate goal of our nature?”

I say both now, and always, shouting out loudly, to all Greeks and non-Greeks, that pleasure is the highest end of life!

The virtues, which are turned upside down by other philosophers, who transfer the virtues from “the means” to “the end”, are in no way the end in themselves! The virtues are not ends in themselves, but only the means to the end that Nature has set for us!

This we affirm to be true in the strongest possible terms, and we take it as our starting point for how men should live.

From here, let us suppose that someone asks a naive question. “Who do these virtues benefit?” “Or, for whose benefit should man live virtuously?” The obvious answer is, “man himself.” The virtues do not make provision for the birds flying past, enabling them to fly well, nor do they assist any other animal. The virtues do not desert the man in which they have been born, and in which they live. Rather, it is for the sake of the man that the virtues exist, and it is for the sake of man that the virtues exert their actions.

I must now address an error that many of you hold; an error that exposes the ignorance of your philosophy even more than your devotion to your false ideas, rather than to Nature. For you reason falsely when you contend that all causes must precede their effects. Because you think that all causes must come before the effects that result from them, you argue that pleasure cannot be the cause for living virtuously. But you are wrong, and Nature shows us that it is not true that all causes precede their effects. The truth is that some causes precede their effects, others coincide with their effects, and still others follow their effects.

First, consider surgery, which is a cause that precedes its effect, the saving of a life. In this case, extreme pain must first be endured, but then pleasure quickly follows.

Second, consider food, water, and love-making, as these are causes that coincide with their effects. We do not first eat food, or drink wine, or make love, and then, later, experience pleasure only afterward. Instead, the action brings about the resulting pleasure for us immediately, with no need to wait for the pleasure to arrive in the future.

Third, consider the expectation of a brave man that he will win praise after his death, as this is an example of a cause which follows its effect. Such men experience pleasure now because they know there will be a favorable memory of them after they have gone. In such cases the pleasure occurs now, but the cause of the pleasure occurs later.

Many men are ignorant of these facts, and they hold that virtue is a result to be desired on its own, and is caused by living in a certain way. These men do not understand that virtues are not results, but causes. Virtues are causes which coincide with their effects, for virtues are born at the same time as the pleasure of happy living which they bring.

[Those of you who do not understand the philosophy of Epicurus, or those who choose to misrepresent it, go completely astray when you fail to understand that pleasure is the end of life. For Epicurus did not hold back from teaching that if a lifestyle of debauchery were sufficient to bring about a happy life, we would have no reason to blame those who engage in debauchery. This is a dangerous teaching for those who refuse to understand it, or for those who misuse the teaching to indulge in the pleasures of the moment.]But where the danger is great, so also is the fruit. We must turn aside fallacious arguments, and see that they are insidious, and insulting, and contrived, by means of games with words and technical ambiguities, to lead unwary men astray. [For the truth is that pleasure is the beginning and end of living happily, and pleasure is the first good that is innate within us. To this view of pleasure as our starting point, and as our goal, we refer every question of what to choose and what to avoid. And to this same goal of pleasurable living we again and again return, because whether a thing brings happiness is the rule by which we judge every good. But although pleasure is the first and a natural good, for this same reason we do not choose every pleasure whatsoever, but at many times we pass over certain pleasures, when difficulty is likely to ensue from choosing them. Likewise, we think that certain pains are better than some pleasures, when a greater pleasure will follow them, even if we first endure pain for time. Every pleasure is therefore by its own nature a good, but it does not follow that every pleasure is worthy of being chosen, just as every pain is an evil, and yet every pain must not be avoided. Nature requires that we resolve all these matters by measuring and reasoning whether the ultimate result is suitable or unsuitable to bringing about a happy life. For at times we may determine that what appears to be good is in fact an evil, and at other times we may determine that what appears to be evil is in fact a good.]

Let us now discuss how life is made pleasant in both mind and body.

In regard to state of mind, we must remember that when an emotion which disturbs the soul is removed, pleasure enters in and takes its place, [for just as nothing can exist in a single place except matter or void, there is no third or neutral state between pleasure and pain where one or the other is not present.]

What are the most disturbing of emotions? Fear of the gods, fear of death, and fear of pain, and also desire which exceeds the limits fixed by nature. These disturbing emotions are the root of all evil, and unless we defeat them, a multitude of evils will grow within, and consume us.

[Just as some men fear the gods, other men, even men as great as Democritus, fear that their lives are controlled by “Necessity,” or “Fate,” or “Fortune.”]To those who adopt Democritus’ theory, and assert that, because the atoms collide with one another, they have no freedom of movement, and that consequently all motions are determined by necessity, we Epicureans have a ready answer, and we ask in reply. “Do you not know that there is actually a free movement in the atoms, which Democritus failed to discover, but which Epicurus brought to light — a swerving movement, as he proves from the phenomena we see around us?” The most important thing to remember is this: if Fate is held to exist, then all warnings and censures are useless, and not even the wicked can be justly punished, since they are not responsible for their sins.

And it is also error to argue that, absent the restraint that comes when evil men fear the gods, or fate, wickedness would have no limit. This is wrong because wrong-doers are manifestly not afraid of the gods, or of the penalty of law, or else they would not do wrong. Those men who are wise, and choose not to do wrong, are not wise because they fear the gods, but because they think wisely, even in matters concerning pain and death. Indeed it is true that, without exception, men who do wrong do so either on account of fear, or because of the lure of pleasure.

On the other hand, men who are not wise are righteous, insofar as they are, only on account of the laws and penalties hanging over them. Only a few men among hundreds are conscientious because they fear the gods rather than the laws. Not even these few are steadfast in acting righteously, for even these are not soundly persuaded about the will of the gods. Clear proof of the complete inability of religion to prevent wrong-doing is provided by the example of the Jews and the Egyptians. These nations, while being among the most religious and superstitious of men, are also the most vile.

So what kind of gods or religion will cause men to act righteously? Men are not righteous on account of the real gods, nor on account of Plato’s and Socrates’ judges in Hades. We are thus left with this inescapable conclusion. Why would not evil men, who disregard the laws, disregard and scorn fables even more?

Thus we see that in regard to righteousness, our Epicurean doctrines do no harm, nor do the religions that teach fear of the gods do any good. On the contrary, false religions do harm, whereas our doctrines not only do no harm, but also help. For our doctrines remove disturbances from the mind, while the other philosophies add to those disturbances.

As we close, do not believe for a moment that all men can achieve wisdom. Not all men desire to achieve wisdom, and not all men are able to seek it out. But for those men for whom wisdom is possible, and who do seek it, such men may truly live as gods. For men of wisdom, all things can be full of justice and mutual love. For men of wisdom, there will one day be no need of fortifications, or of laws, or of all the other things we contrive on account of fear of one another. Such men will be capable of deriving all their necessities from agriculture, without need of slaves, for indeed the wise man shall tend his own plants, and divert his own rivers, and watch over his own crops.

Fear of the gods; fear of death; fear of pain; fear of slavery to those desires which are neither natural nor necessary. The day will come when none of these shall interrupt the continuity of our friendships, and of our happiness, in the study of philosophy. In that day, wise men will tend the Earth, in a life close to Nature; our agriculture will provide for our needs, and we, and those who are our friends, will live as gods among men.

And Thus Ends the Inscription of Diogenes of Oineanda.

This presentation of the Inscription of Diogenes of Oinoanda has been a project of New Epicurean.com, August, 2013. It has been based on the translations of Martin Ferguson Smith an C. W. Chilton rendered into modern American English, and organized for audio presentation. The student of Epicurus should consult the original translations for comparison, and also consult the ultimate authority, the inscription in its original Greek.

For further information about this presentation, please visit NewEpicurean.com.

Peace and Safety!